Emotions Play a Part in the Design Process

by Monica Biagioli

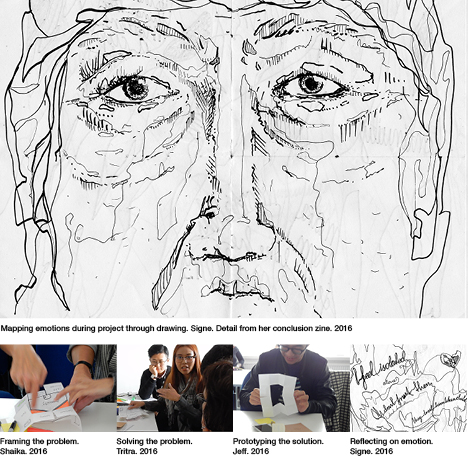

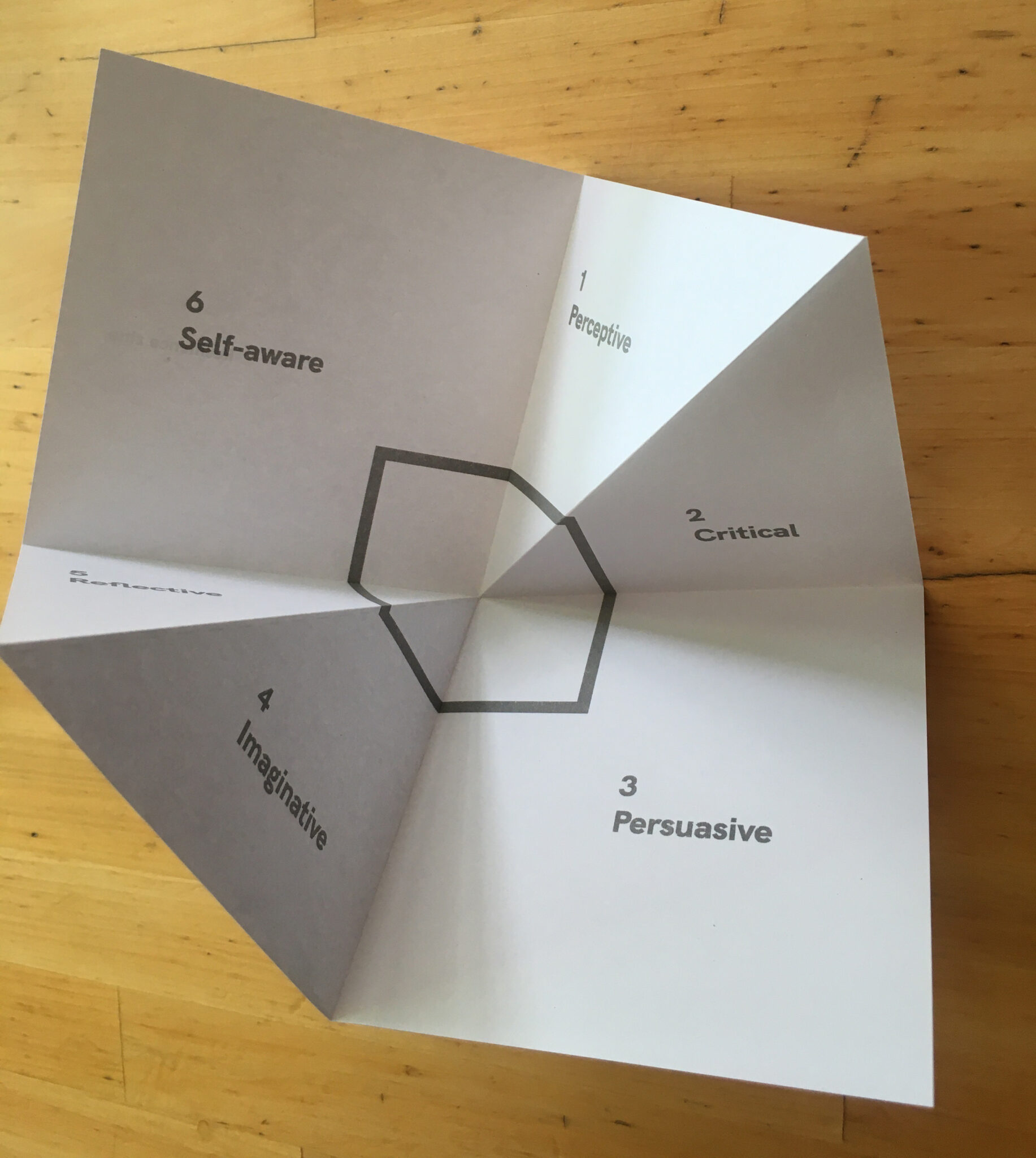

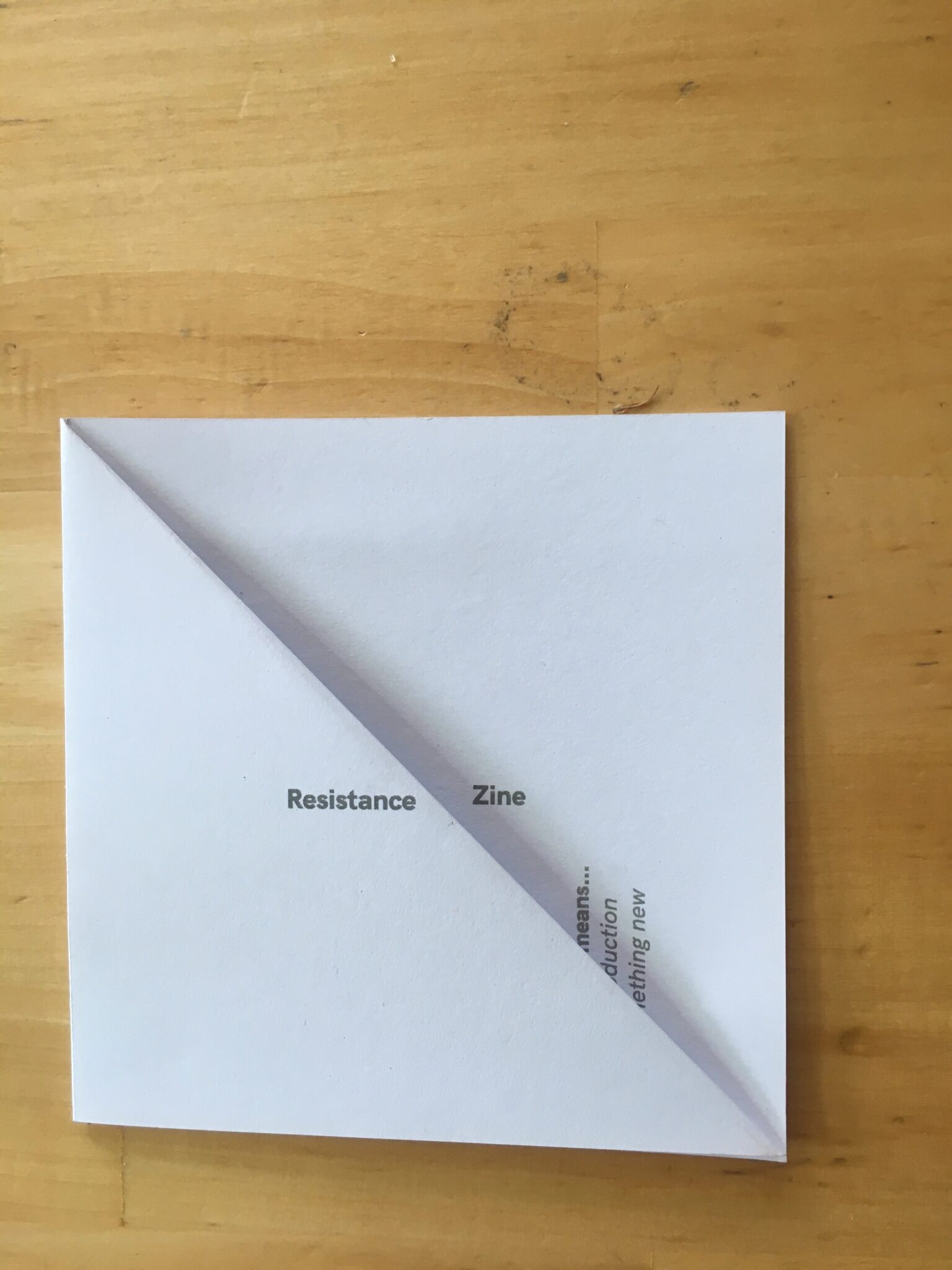

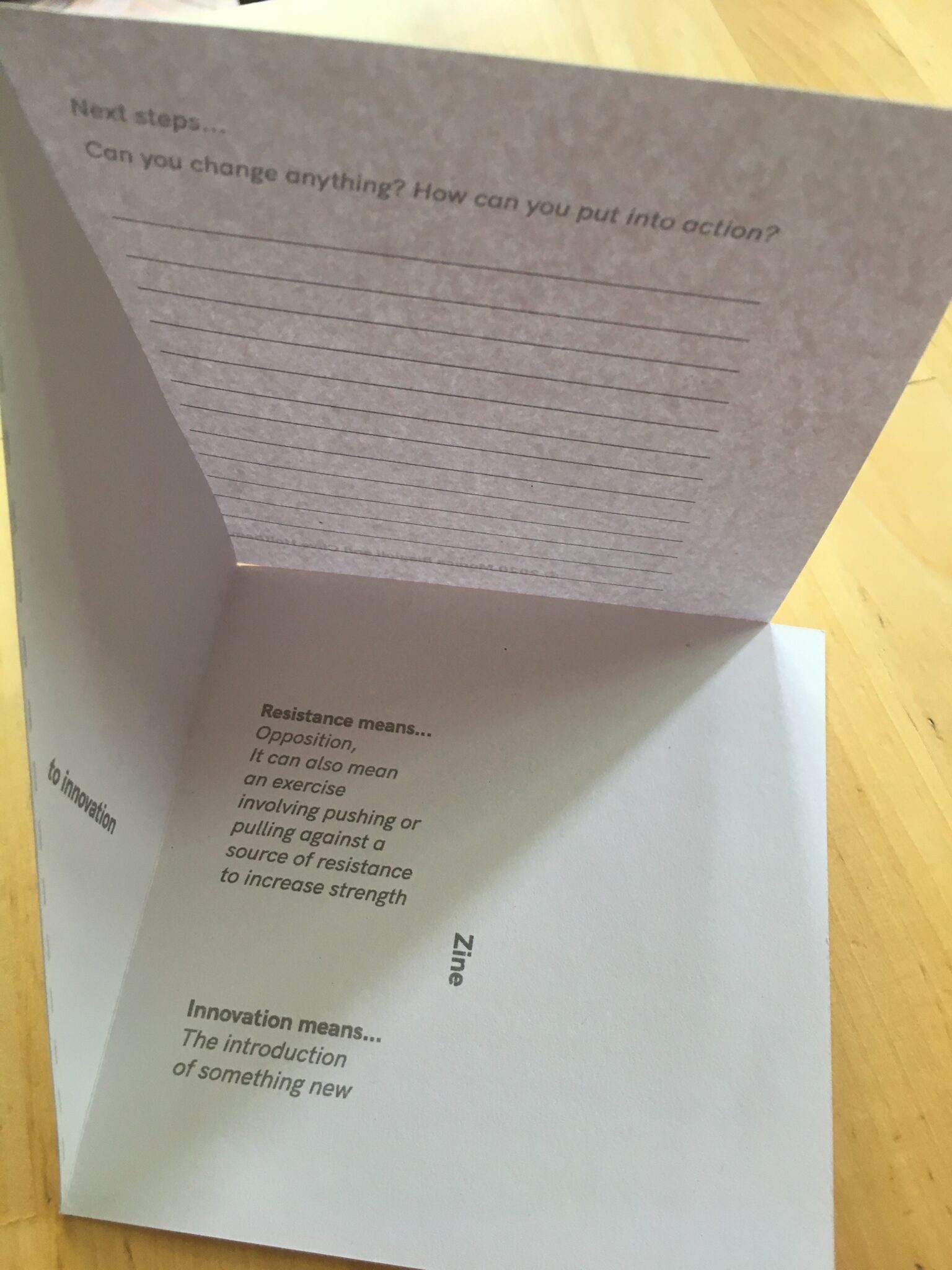

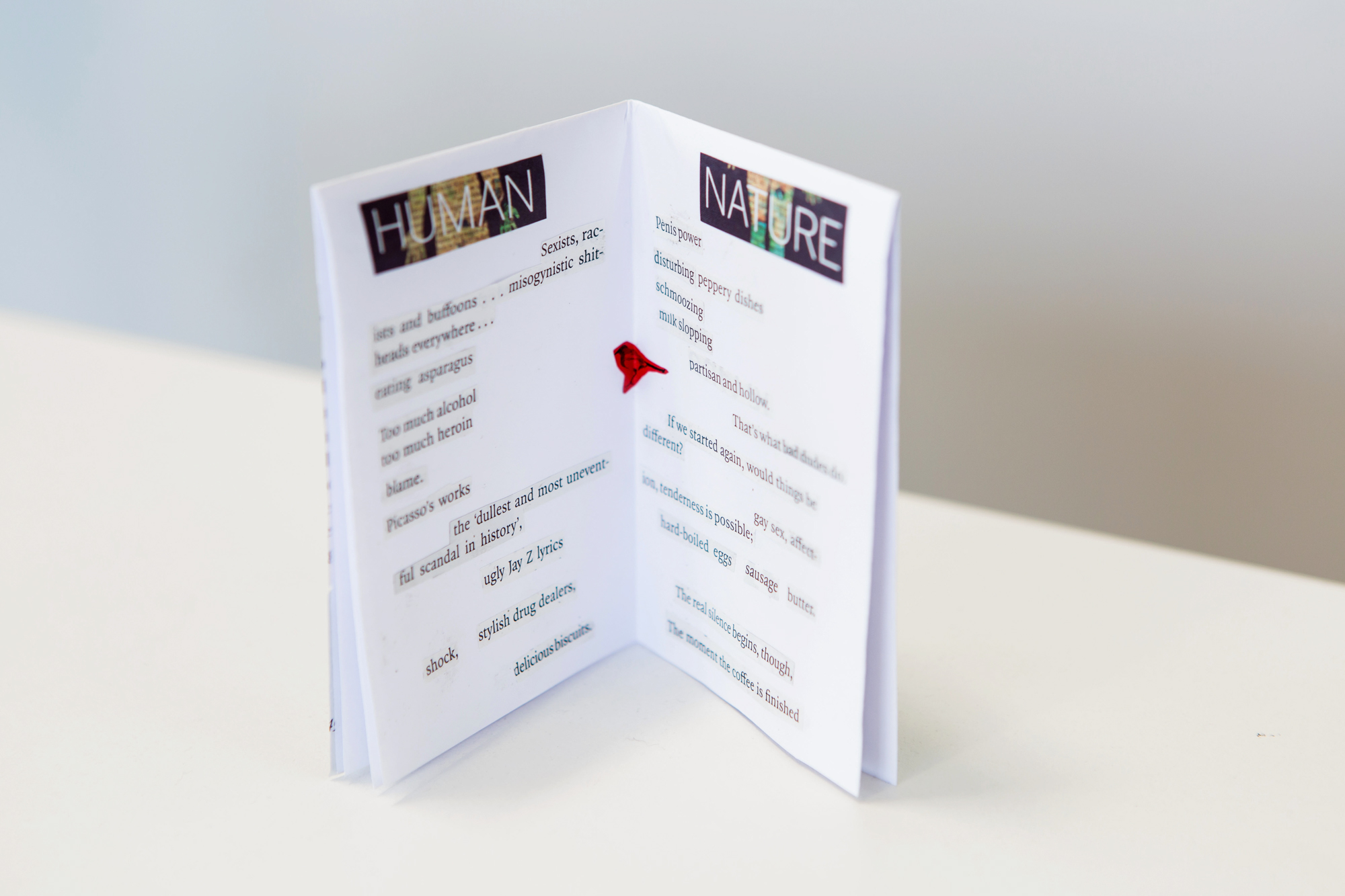

An area of interest to me is the role emotions play in the design process. Designers are not neutral. They have emotions, perspectives, and ways of working that are varied. This interest emerged during a research project where as part of a research team I tested a methodology from the graphic arts with students in a masters’ service design programme. I provided various zine formats — folded multi-page constructions — for students to apply in the process of project development. My thinking was that they would use zines to model the problem area or as a communication tool in discussions within their design teams. This they did. But there was one application that emerged that I had not anticipated.

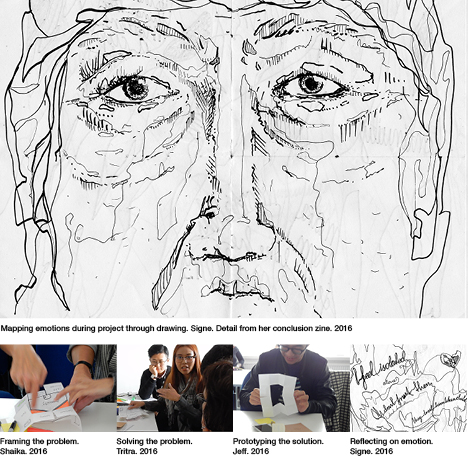

These students, working on service design projects, were experiencing a variety of emotions as they engaged with people and places and the difficult situations they often encountered. These are referred to as ‘wicked problems’ because they tend to be complex, sticky, and difficult to unpack into simple problem-solution frameworks. Within their project construction, there was no mechanism in place to account for their own emotions in the design process. So during our research session, they used the zine templates I provided as a contained space to hold various thoughts and feelings that emerged in their minds in relation to the projects they were currently working on. The zines could fold down, and in that way, actively and physically contain the emotions. They also served as a private space for reflection during a process. They could be used at various stages of project development to reflect on one’s own process within a team project.

During this research session the formal expectations of a design process and the actual informal effects of that process on the individual designer came into focus. The importance of reflection in the iterative design cycle came into shape as well.

The experiential and emotional domain of designers’ practice is not often acknowledged as part of the process of coming up with solutions and outcomes. Tacit experiential knowledge is by nature informal, something felt but difficult to express explicitly in design decision-making.

As a research team, we took this insight further and wrote an academic paper to explore the dimensions involved in accounting for designers’ emotions during a design process. Would it be possible to demonstrate any links between designer emotion and decision making in a design process? If we could, as designers, access this type of tacit information—belonging to the informal realm, characterised by complexity and ambiguity, and expressed as emotion—then its impact on rational decision-making could be acknowledged.

This approach questions the assumption that the designer is neutral within a design process. From the research team’s teaching experience, design students have complex relationships with their project especially when they tackle “wicked problems” (Buchanan, 1992; Rittel & Webber, 1973). Some of these projects generate strong emotions and feelings in the designer, such as empathy, sadness, anger or a feeling of empowerment, and this has a bearing on the project outcomes. In that academic paper we drew attention to qualitative methods because they allow for gathering information, such as tacit experiential knowledge and emotional states. This type of information may not be visible in data set analysis, but it has an impact nevertheless on project planning, audience engagement and design outcomes.

Our aim there was to account for the informal, the non-textual, the narrative and the emotional that exist in the liminal space between formal analysis of data and formal design decision-making. To make what is felt in a design process explicit, and therefore, to recognise how it might affect project development and decision-making.

Qualitative design and arts-based methods have a particular value for accessing informal, non-textual, narrative, and emotional elements and making them tangible. These qualitative design methods are often applied to researching the end users’ emotions, but rarely are they used to look inwards towards the designers themselves.

Emotion is in the informal domain and accounting for its role in a decision-making situation requires an acknowledgement of embodied experience. There is a current bias towards quantitative forms of collecting and analysing experience in order to make the case for making decisions. This approach tends to omit findings from the informal experiential range, as they are so difficult to quantify.

As the world of work evolves to make room for robotic components and algorithmic computation to input into decision-making and realise more and more complex tasks, it is increasingly important to consider the organization’s view of their workers as embodied persons. Giovanni Schiuma argues that “organizations have to be managed as ‘living organisms’ in which the people and the organizational aesthetic dimensions are recognized as fundamental factors to meet the complexity and turbulence of the new business age.” (Schiuma, 2011, p. 2) For that, Edward T. Hall’s diagram of human activity is highly relevant. He deduced a system of understanding human activity in three porous layers: formal, informal, and technical (Hall, 1959). The formal layer is occupied by expectations, values and structures; those values and structures are shaped into more codified forms (rituals, language, protocols) in the technical layer; and the informal layer is where shifts can happen and is the terrain of gesture, play, informal learning, and a sense of individual

space and beliefs.

It follows that accounting for the informal requires an acknowledgement of embodied experience. As John Dewey explained it: “Experience is the result, the sign, and the reward of that interaction of organism and environment which, when it is carried to the full, is a transformation of interaction into participation and communication.” (Dewey, 2005, p. 22). For Dewey, there were complete experiences, holding transformative and aesthetic potential and characterised by feelings of satiety and fulfilment, and inchoate experiences, obstructed by distraction and dispersion. The many layers of diversion and entertainment broadcast from various media sources create a level of inertia that Daniel Boorstin identified over 50 years ago as a visual gauze, at the time when mass media lodged into the North American consciousness. This disjunction between what is communicated (and how)

and what is experienced leads then to more frequent inchoate experiences; dispersed and

incomplete.

The result, as Iain McGilchrist identifies, are various current maladies: “loss of tolerance of

ambiguity; the carrying out of procedures by rote without understanding; de-individualisation; paranoia and lack of trust; a worship of the quantitative and devaluation of quality; and downgrading of expertise and its capacity to react with spontaneity and creativity in favour of ‘expert’ knowledge that can be pre-determined” (Holmes, 2012, p. 163). This loss of faith in more holistic, embodied forms relates to our current means of communication that shape as well our sense of identity (McLuhan, 1964).

In their book on the social impact of the arts, Belfiore and Bennett account for our growing reliance on evidence to make the case for policy; with “hard data, such as facts, trends and survey information…widely seen as the ‘gold standard’“ (Belfiore & Bennett, 2008, p.5). The subtext riding below the surface of this approach is that qualitative forms of analysis cannot be trusted to formulate decisions. Satinder Gill sees it as a situation where “the paradigm of data (of parts) and utility gives primacy to transactional information over that which is relational.” (Gill, 2015, np). She addresses “the problems of bottlenecks of vast quantities of data and how to relate to them (expert systems, databases, big data), and how to support our relations with each other and share and enable us to impart knowledge and skills when we are distributed in space via various mediating interfaces” (Gill, 2015, np).

As Michael Polanyi cautions, “if we build up a culture recklessly on the assumption that only things are valid which can be broken into parts – and that the putting together will take care of itself – we may be quite mistaken, and all kinds of things may follow.” (Polanyi, 1989, quoted in (Gill, 2015, np))

Drawing attention to qualitative methods and more explicitly accounting for tacit experiential knowledge and emotional states—not just in participants and end users but also in designers and facilitators —can address this imperative to consider societal problems and needs holistically.

Qualitative methods allow for more complex, sometimes contradictory findings to emerge. More importantly, they account for the human factor in a situation or process. How is a process feeling? becomes a relevant question and one that when answered also requires consideration in the approaches suggested as responses or solutions. It really comes down to value. If we value the human experience and response in a situation then we will consider the emotional impact on those affected as an important and relevant factor in evaluating success and ways forward. The design process is iterative in nature, and considering emotion and tacit experiential responses as part of this ensures that the emphasis of our effort as designers is to improve and enhance human experience through design.

References

Ali, Hena and Grimaldi, Silvia and Biagioli, Monica (2017) Service Design pedagogy and effective student engagement: Generative Tools and Methods. The Design Journal, 20.

Belfiore, E. and Bennett, O. (2008). The social impact of the arts: an intellectual history. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Biagioli, Monica and Grimaldi, Silvia and Ali, Hena (2018) Designer’s emotions in the design process. In: Design Research Society 2018: Catalyst, 25-28 June 2018, Limerick, Ireland.

Biagioli, Monica and Holtham, Clive (2020). Thinking by Making: Applying the zine method for management learning. University of the Arts London, London, UK.

Biagioli, Monica and Pässilä, Anne and Owens, Allan (2021) The zine method as a form of qualitative analysis. In: Beyond Text. Intellect Books, Bristol, UK.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

Gill, S. (2015) Tacit Engagement: Beyond Interaction. London: Springer.

Given, L.M. (Ed.). (2008) The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Vols 1 and 2. London: Sage.

Hall, E. T. (1959) The Silent Language. New York: Doubleday.

Holtham, C. (2016) Keynote Speech, IFKAD, Dresden, 2016.

International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynamics (2016) Towards a New Architecture of Knowledge: Big Data, Culture and Creativity. Conference Program. https://www.ifkad.org/previous-editions/ifkad-2016/. Accessed 10 December 2018.

Laing, R.D. (1960) The Divided Self. New York: Pantheon Books.

McGilchrist, I. (2009) The master and his emissary: The divided brain and the making of the western world. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Radovic, D. (2014) ‘Measuring the non-Measurable – On Mapping Subjectivities in Urban Research (and several themes for discussion)’, paper presented at Mapping Culture: Communities, Sites and Stories conference, Coimbra, Portugal, May 2014.